Children of the Vault #4 annotations

As always, this post contains spoilers, and page numbers go by the digital edition.

CHILDREN OF THE VAULT #4

CHILDREN OF THE VAULT #4

“Kill the Future!”

Writer: Deniz Camp

Artist: Luca Maresca

Colour artist: Carlos Lopez

Letterer: Cory Petit

Design: Tom Muller & Jay Bowen

Editor: Sarah Brunstad

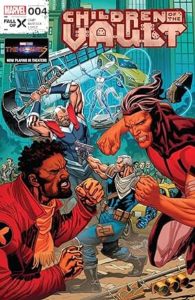

COVER / PAGE 1. Cable and Bishop fight the Children of the Vault.

PAGE 2. Cable threatens to shoot the City.

This is where we left off last issue.

PAGE 3. Recap and credits.

PAGE 4. Rodrigo Muñoz reacts – kind of – to the battle.

We saw Rodrigo before in issue #1. He was the kid wandering around the lithium fields just before the City showed up overhead.

As Martillo explained in issue #2, the Children’s “Message” transforms people “first in mind, then in body”; most humans will die in the process, but the tiny minority who survive will become Children of the Vault. Clearly, Rodrigo is some way into his transformation.

“Tierra Desnuda”, the name of Rodrigo’s Children-built “Tomorrow Town”, was previously given in issue #1.

PAGES 5-6. Muerte appears on the Orchis Reforge.

Madre despatched Muerte for this mission in the previous issue. According to Madre, the Children had stopped cloning Muertes because they caused so much indiscriminate damage, but “the time again call for murder and megadeath”. She handed Muerte the object he’s holding here, evidently some sort of weapon. We’re not told directly how he got onto the Reforge, but presumably one of the Children will have teleporting powers – perhaps Muerte himself. Since he doesn’t appear to use any powers to destroy the Forge, it may be that what suits him for this role is just a willingness to destroy himself and others.

Of course, Orchis now seems to work mainly from its orbiting space station rather than from the Orchis Forge (original or rebuilt), but the loss of this thing is still a significant setback for Orchis. In terms of the timeline, it’s maybe worth noting here that Children of the Vault #1 gives the time frame as “weeks later”, and not “X weeks later” as in most other “Fall of X” books. It also says that Cable has been an Orchis prisoner for “over a month”. Since X-Men Red places “X week more explicitly as 10 weeks, it seems to be possible for this whole series to take place during the “X weeks” gap, which would explain why the Children’s actions haven’t been referenced in other titles.

PAGES 7-8. Cable confronts Serafina and Capitán.

The footnotes already refer to the first Children story, and specifically X-Men #193, where Serafina briefly traps Cannonball in a simulated life together with her.

Cannonball died at the Hellfire Gala along with the rest of the new X-Men team. His wife, Smasher, hasn’t shown up since, but presumably has views on the subject, which might become relevant if Alpha Flight ever succeed in evacuating any mutants to the Shi’ar Empire.

Cable says that he’ll “work with whoever I have to… the devil himself”, which most obviously refers here to him teaming with his former arch-enemy Bishop. He does in fact refer to Bishop as “the devil himself” when he shoes up on page 12.

PAGE 9. More humans collapse in response to the Message.

PAGE 10. Luz kills from Orchis soldiers.

The narrator alludes to Luz being one of the more sympathetic Children, which indeed she was in her earliest appearances, X-Men: Legacy #238-241. She starts off as an artist rebel trying to escape her predetermine role in the Children, and was set up as a potential love interest for Indra.

PAGE 11. Data page. In issue #2, the data pages were excerpts from “the Tetrahedral Histories of Diamante, the Flawless Memory, the-Brilliant-Breathing-Record”. Apparently those pages should now be read as representing the official history of the Children, because this page comes “from the Anti-Histories of Diamente, the Hidden Facets, the Flawed Libraries”. Basically, it’s a basic cultural premise of the Children’s society that they are the destined rulers of the world, and Diamante is acknowledging the fact that this belief sits very awkwardly with their abysmal win-loss record. Of course, the Children’s official answer to this objection is that they just need more evolution and they’ll get there in the end.

The Conquistador was the old tanker where the Children’s time-dilating Vault was located in their first appearances, starting in X-Men #188 (2006).

PAGES 12-13. Bishop arrives to help Cable.

Capitán clearly buys in to the idea of the Children so fundamentally that he can’t really understand any other worldview. Bishop spells out for us that the X-Men’s two paramilitary time travellers are not at all put off by the idea that they’re fighting “the future”.

PAGE 14. Diamante is consumed by his flaws.

Presumably, this is connected in some way to the error which the City reported in the previous scene – perhaps because the flaw which he has always suppressed (as explained in the next data page) is now coming to fruition.

PAGE 15. Data page: Diamante expands on the previous page, essentially saying that the reason why the Children always fail is because their society, however highly developed, started on a flawed premise. He has suppressed this insight because (he believes) the Children’s society could not survive coming to terms with it.

“Poor, desperate Sangre, struggling to be heard on the steps of the Foro…” In issue #2, Diamante’s official history reported: “Every Citizen watched Sangre-142 tear himself apart on the steps of the Gran Foro to make a point. The City wept that day, but the point was lost.” Apparently, that version of Sangre did recognise that the Children had no right to lay claim to the world, and his attempt to make that argument was suppressed.

PAGES 16-22. Cable and Bishop intimidate Serafina into surrendering.

Cable has infected the City with a strand of the techno-organic virus from an alternate future, which he is able to control thanks to his years of training with his own T-O infection.

“That’s why, when they brought me back from the dead, I insisted it be with my virus.” This was indeed the first thing Cable asked about when he was resurrected in Cable #11 (2021).

“Bishop here picked it up a week ago.” In issue #2.

Babel Spires. This is indeed the standard life cycle of a techno-organic infection; it was the central plot of the 1990s “Phalanx Covenant” crossover, and most recently came up over in Legion of X.

Madre was attacked by Bishop last issue, and this scene makes clear that she was deliberately targetted in order to threaten the Children’s ability to clone future generations.

Bishop alludes to the fact that he committed far greater atrocities than this during the Cable solo series where he was pursuing Hope through alternate futures, something that most writers have tended to run a mile from. Deniz Camp is unusual in embracing it as an aspect of Bishop doing literally anything that he considers necessary. Of course, the Children don’t know anything about this (presumably), but Bishop and Cable are indeed unusually well placed to make the credible claim that they simply do not care about conventional X-Men moral values – certainly when up against the Children trying to kill 99%+ of the planetary population.

Serafina ends the series by, rather bitterly, objecting that all Bishop and Cable ever had to offer the human race was “projection after projection of their impending demise” – i.e., an endless series of stories about apocalyptic or post-apocalyptic futures. They’re not just time travellers, but they embody a fundamentally pessimistic – almost nihilistic – sub-genre of superhero comics, where the future is always dismal. To Serafina, a world where 99%+ of humanity gets wiped out and the rest join the Children is still an improvement on anything in Bishop and Cable’s continuity.

“What is, is” was the Askani mantra in various 90s Cable stories.

The narrator tells us that once the “Message” is defeated, “something else rushes in to take its place” – apparently Orchis. This seems to confirm that Children of the Vault takes place during the time jump made in the other “Fall of X” books.

PAGES 23-24. The Children retreat back to the Vault.

Serafina throws in a warning that something even worse is coming, and the humans will just die from that instead.

Orchis are shown holding a victory parade after claiming credit for the defeat of the Children; Killian Devo is the guy waving to the public.

We end with an image of a sickening Rodrigo Muñoz, with the news reporting that the degrading Tomorrow Towns have turned toxic. Bear in mind that the series opened with Muñoz in a poisoned landscape already, and if he’s one of the humans who would have survived the transformation – as his scene earlier in the issue seems to suggest – then in a sense he was robbed of a better future by the Children’s defeat. I mean, aside from the point where all his friends and family would have died…

PAGE 25. Trailers. Since this is the final issue, we’re directed to X-Men #29. The Krakoan reads FOLLOW THE FALL.

I liked this. The scenario depicted is in basic outline the future as shown in Moira’s prior lifetimes, where post-humanity is inevitable. We saw the alternative for humanity as being conquered by mutants (hopefully, they will be merciful rules, as stated by Xavier, rather than the alternative) and waiting to go extinct.

Moira’s Life Six featured an utopian vision for humanity (the elect who become post-human), only marred by the fact that they had not prepared properly for a “predator race” from space (the Phalanx) and the fact that they were tempted by a literal immortality. Unfortunately, that world also meant a dystopian world for mutants, although seemingly the same “benign” one envisioned for humanity by mutants in the alternate Life 10. Humanity turned to genetic engineering to breed the X-gene out of the Homo Sapiens Sapiens genetic pool and kept the surviving mutants in a zoo.

Of course, superheroes/the X-Men are trying to fight for a more hopeful future. Is their optimism realistic? Is the pessimism of Moira (before her character got butchered) more rational?

We saw the eventual establishment of an utopian world for humanity in Life Six. Yes, it could be argued, it had to be erased due to the fact that the end point was the Dominion. Yet, what did we see in Moira’s Life Nine? The victory of post-humanity over mutants again, but this time at the expense of having to be slaves to the machines far earlier than Ascension.

Which takes us beyond this mini-series, but touches upon what Serafina had to say at the end, about “something worse coming”. Left to it’s own ends, the final point of evolution seems to be the mechanical. It was only through the machinations of Moira that Ascension was averted. So, Serafina wanting to see the victory of post-humanity and pointing out what is coming will be worse for both humans and mutants may also be going against the inevitable. Maybe Machine life is the simply the end point of evolution.

Granted, we’ll most likely see something less rigidly deterministic from the Krakoa-era in the end.

The point, of course, is that if the Children had actually tried to help humanity in good faith, both humanity and the Children could have benefited but the very nature of the Children’s society makes it impossible for them to imagine a future where they don’t exterminate or rule humans.

“Of course, the Children don’t know anything about this (presumably)”

The Children knew what Bishop and Cable were capable of because of Serafina’s powers.

The threat Serafina was warning about was the Dominion, which she sensed last issue.

Michael-Isn’t there a question about that? Think about the alternate Life 10, where humanity and mutantkind formed an alliance against the Children. After the two sides saw they could mutually work together (although for aggression, but still self-preservation), Krakoa discovered that humanity was still deciding to build a Nimrod, leading to another war.

There will always be those forces who want to see the status quo maintained and will oppose change/anything different, which is what the post-human future offered by the Children would entail (whether offered peacefully or through malevolent subterfuge).

I find the message is one about a choice between stopping fighting and letting the inevitable take place, if there is any hope of an eventual utopian future…whether that entails one for humanity/post-humanity, mutants, or machine…or fighting the future, continuing to hope that there is a better alternative (Xavier’s dream), which may be a total impossibility, even though that may entail (even unintentionally) supporting the status quo, while people like Rodrigo end up being forgotten and lost.

The idea that Orchis is on some level filling a gap that the Children created makes the slightly incomprehensible aspects of the response to Orchis make a little more sense. Not in a way where it totally fixes the issues but at least it minimally addresses them.

I’ve figured out what’s bothering me about this era. I can accept the concept of people fearing replacement by mutants. It’s the generation gap writ large, as sung by Bowie. But the idea of it being a struggle whether my great-grandkids will be eternal cyborgs or atomic supermen, if just feels really low stakes to me. Especially since, with characters like Forge and Cable, it’s obvious that my great grandkids could be both at once.

The Children of the Vault killing almost everyone is a different story of course.

Yes. That’s what I’m getting at, that it’s played as a zero-sum game. That it’s somehow important that mutants are immortal or humans are immortal. Look at Moira’s sixth life. Humanity has its time, but eventually it gets replaced by post-humanity. In that gap between baseline humans and Homo Novissima, mutants have a pretty good run. Then, their time is over, and post-humanity creates their own utopia. They live it up for their allotted timespan, and the Phalanx come around. Now, flesh gives way to machines, which truly have the potential to be immortal as information within a Dominion.

I am perfectly fine with all of that. It’s Pierre Teilhard De Chardin’s philosophy being lived out.

To me, it doesn’t matter if the dominant lifeform on Earth is Homo Sapiens Sapiens, the next race of man that humanity gives birth to, what comes next in Homo Sapiens Sapiens’ evolution, or the technology created by humans. The quality of life is what is important. If Homo Sapiens Sapiens is to be replaced someday by something better, so be it. If Homo Superior is to be replaced someday by something better, so be it.

Chris V > Moira’s Life Six featured an utopian vision for humanity (the elect who become post-human).

That’s not how I read it. The humans were completely extinct by Year 1000 of Moira’s Life 6. The mutants were near-extinct, and kept in a preserve. The posthumans ruled the world and their servant machines helped to maintain it.

Posthumans are not the same species as humans, they are not simply humans with cyborg implants, they are the end stage of multi-generational transhuman + machine breeding/synthesis. They are a new species entirely – homo novissima (the last man), as opposed to homo sapiens (the wise man). If this miniseries had ended with the CotV (the Life 10 posthumans) ending humans and mutants entirely, would that have been a utopian vision of humanity?

I also don’t agree that (at least in the Life 6 future) the posthumans had not prepared properly for the Phalanx. They called the Phalanx to Earth in the first place by using the Nimbus Worldmind as bait. Homo novissima was an evolutionarily stagnant species, they required synthesis with a higher form of machinekind to kick-start their evolution into a new species. The Librarian’s problem was not that they were caught unawares by the Phalanx, he had a moral quandary about what post-posthuman existence might look like.

Here’s my reading of Powers of X. There are three “species” in competition for control of the world – mankind, mutantkind and machinekind.

In a typical Moira lifetime:

In Year 1, humans rule the world. Mutants and machines – the two children of mankind – are quickly evolving while humans begin to evolutionarily stagnate.

In Year 10, mutants, either individually or collectively, begin to advance their causes on a global scale. In response, the humans and the machines form an alliance to counter the mutants. This alliance is skewed heavily in favor of the humans, who create and program slave machines that work for them. This lopsided balance will not last.

In Year 100, machines rule the world. Once the mutants are gone, the power differential between humans and machines leads the machines to take over completely. A tiny fraction of humans merge with machines to survive, which eventually gives rise to posthumanity.

Moira Life 9 is a Year 100 scenario. Nimrod and Omega Sentinel lead the Man-Machine Supremacy and rule the world. The human mutant-hunters are slaves and treated as such. The mutants are endangered on Asteroid K. The fringe Church of Ascendancy is a burgeoning posthuman group, one that is ignored by Nimrod as he considers them irrelevant. A mistake on Nimrod’s part.

Days of Future Past is another Year 100 scenario. The machines rule the world, the humans live under machine rule, and the endangered mutants live in a concentration camp.

In Year 1000, posthumans rule the world. The machines, once slaves of the humans, then rulers of the world, have become slaves of the posthumans. We see this in Moira Life 6. Nimrod the Greater is a personal assistant to the posthuman Librarian. The mutants are near-extinct in a preserve. The humans are extinct.

At a certain point in their reign, the posthumans begin to evolutionarily stagnate as the humans once did.

Here’s my reading of House of X.

In Moira Life 10:

The Xavier-Moira alliance was the beginning of Year 1: The Dream. Mutant leaders began to form groups such as the X-Men, the Brotherhood, the Horsemen, etc. to advance their mutant agendas while humans began to build Sentinels to work for them.

House of X was the beginning of Year 10: The World. Professor X, Moira X and Magneto achieved their dream of the mutants of the world uniting under a single banner to advance their cause in unison. In response, humans and their servant machines formed Orchis, the Life 10 version of the Man-Machine Alliance.

Fall of X was the beginning of Year 100: The War. Orchis attacked Krakoa, leading to the scattering of the mutant nation. They planted the seed of discord on Arakko, leading to civil war on the mutant planet. We have hints that mainstream Orchis won’t stop at mutants and plan to eradicate all other superhumans. We know from Inferno that Orchis’s true founder, Omega Sentinel, plans to kill all humans, including Orchis, once the mutants are gone.

It stands to reason that Fall of the House of X / Rise of the Powers of X will be the beginning of Year 1000: Ascension. We have multiple species vying for Dominion to bring an end to the man-mutant-machine war. The human faction (the four Essex clones) have been pursuing four different paths to Dominionhood. We have evidence one of them may have succeeded in a prior timeline. The machine faction (Omega and Nimrod) plan to attract a Phalanx and join a traditional machine Dominion. And there is the mutant faction displaced in the White Hot Room, where a plan for a mutant Dominion may yet emerge. A plan that works now and forever.

There was this interesting comment from the issue 1 annotations that I wanted to contribute to.

Chris V > Now, this comic adds even more questions about Orchis. If the Children of the Vault are post-human, shouldn’t they represent what Orchis is hoping to achieve. Are the Children of the Vault potential enemies because they aspire to Ascension, as in Moira’s Life Six?

The mainstream majority of Orchis (Dr. Gregor and the scientists, the S.H.I.E.L.D. agents, the A.I.M. agents, the Hydra agents, etc.) is a human supremacist organization. To them, posthumans are just as big a threat to human existence as the mutants. In Hickman’s X-Men 1, Orchis scientists had Serafina imprisoned in an experimentation lab along with other mutant children. They either didn’t know she wasn’t a mutant or they didn’t care.

The fringe machines (Omega Sentinel, Nimrod) are machine supremacists pretending to be loyal human tools. To them, humans are just as big a threat to machine existence as the mutants. They are waiting for Orchis to neutralize the mutants so that the machines can neutralize the humans. But despite appearing to be servants, the machines are secretly in control of Orchis because Director Devo is Omega’s pawn.

Dr. Stasis is a posthuman enthusiast pretending to be a human supremacist. He advances Orchis’ science causes but his secret agenda is to personally ascend to Dominionhood through posthuman exploitation. He has secret ties to the Children of the Vault as seen in The Sinister Four.

M.O.D.O.K. is just an A.I.M. supervillain that Orchis has a given a bigger platform to carry out his schemes. Note that he was experimenting on his mind control drugs on a smaller scale by himself in X-Men 8 before Orchis recruited him. The same is true of the new Captain Krakoa. A Hydra supervillain that Orchis recruited to advance their cause.

@Chris V: Point of order, Life 6 was *not* the mutants having a “good run”, the Librarian makes it clear that they were exterminated. “Sentinels bought us years, Nimrods bought us decades.”

Whatever happened to Darwin, who was supposed to be staying in The City to keep tabs on the Children?

@Rob- it was STRONGLY implied that he escaped the Vault through Forge’s mind in issue 17. And then that was never mentioned again.

I found this quite fascinating in terms of the lengths it goes to to justify monstrous actions on Bishop and Cable’s part. It was very fascist in a way that’s unusual for X-men; of course X-men has always portrayed the opponents of mutants as nigh-uniformly genocidal monsters united in their hate for the superior species, but this is I think a crucial step in that Bishop and Cable in turn consider it justifiable to do anything to stop their enemies-kill the humans, kill the children, kill everything-and are not truly condemned by the narrative; rather it is portrayed as the natural outcome. It feels like a bridging point, like something is coming out of the morass of X-men metaphors and writers in the same way as Krakoa.

Muerte’s suicide bombing scene here is an homage to the “Death” bombing scene from Hickman’s Ultimates. Hickman made “The City” as an analog to Carey’s “the Vault”

I’ve been wondering how many people cheering Cable and Bishop when they commit war crimes are condemning alleged RL war crimes. Could Bishop and Cable’s attack on the Vault be considered collective punishment?