Daredevil Villains #41: Black Spectre

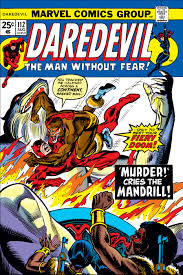

DAREDEVIL #108-112 (March to August 1974)

DAREDEVIL #108-112 (March to August 1974)

“Cry… Beetle!” / “Dying for Dollar$!” / “Birthright!” / “Sword of the Samurai!” / “Death of a Nation?”

Writer: Steve Gerber

Penciller: Bob Brown (#108-109, 111), Gene Colan (#110, 112)

Inker: Paul Gulacy (#108), Don Heck (#109), Frank Chiaramonte (#110), Jim Mooney (#111), Frank Giacoia (#112)

Letterer: John Costanza (#108), Artie Simek (#109-110), Tom Orzechowski (#111), Annette Kawecki (#112)

Colourist: Petra Goldberg (#108-109, 112), Linda Lessmann (#110-111)

Editor: Roy Thomas

There are several noteworthy things about the Black Spectre arc. On the most basic level, it takes the book back to New York. Foggy Nelson, who we haven’t seen since issue #87, has been shot by a sniper, and Matt Murdock returns to Manhattan to help out. At first, the story presents this as a brief visit. But Matt won’t go back to San Francisco until issue #116, and even then it’s just to tie up loose ends. The reality is that from issue #108 onwards, this is a New York book again.

As for Moondragon, who was introduced with great fanfare in the last story, she’s instantly written out.

But that’s not the most striking thing about the storyline. Until now, Steve Gerber’s Daredevil has been a fairly normal comic, at least by the standards of Steve Gerber. Sure, there’s Angar the Screamer and his LSD powers. But the book has mostly stayed within normal Marvel parameters. Even when it’s ventured into stranger territory, it’s drawn on Jim Starlin concepts.

The Black Spectre arc is much weirder, for both good and ill. Its villains proved to have more staying power than most new characters from this period of Daredevil, but from the standpoint of 2024, there are aspects of this story which could generously be described as “questionable”. In fact, “staggering” might be closer to the mark. A handful of comics on Marvel Unlimited have content warnings, of the “This comic is presented in its original form” variety. This arc doesn’t, but it probably should. “This comic is presented in its original form. It reflects the editorial standards, racial politics and recreational pharmaceuticals of 1974. Reader discretion is advised.”

We need a bit of back story here. The Black Spectre storyline was picked up from a cancelled book. Shanna the She-Devil had been launched in 1972 in an attempt to revive the jungle girl genre. Eventually Shanna herself was repositioned as Ka-Zar’s partner, and so she came to be associated mainly with the Savage Land. But at this point she’s an American woman in a leopardskin bikini who protects an African game reserve. The writer who created her was Carol Seuling, but Steve Gerber had helped to script her early appearances.

Shanna #4, plotted by Seuling and scripted by Gerber, introduces the Mandrill. He first appears as a hooded man who tries to enlist people in a scheme to overthrow three African nations. Everyone thinks he’s mad, so he reveals that he has the head of a mandrill, which is somehow meant to convince people that he’s a winner. He claims to lead a “religion of hate”. He’s accompanied by two female worshippers who have mandrill tattoos on their faces. He also turns out to have kidnapped Shanna’s father, which was the main plot of the book, thus positioning him as Shanna’s arch-villain. But there’s no mention at this stage of any mind control powers, and Shanna simply fights him and wins.

Issue #5 is credited to Gerber alone. The Mandrill doesn’t appear, but his partner Nekra makes her debut as the chalk white priestess of his aforementioned hate cult. She has a whole congregation of African women with mandrill face tattoos, who yell a lot about hate, and she seems to get superhuman strength and invulnerability through the power of their rituals. Professor X shows up briefly, to confirm that Mandrill and Nekra are both mutants.

There is no issue #6. Shanna the She-Devil was not a success.

But about six months later, Gerber brought back the Mandrill and Nekra in Daredevil. Shanna also guest stars in this arc, in order to tie up her dangling plot threads. To be honest, though, the plot would play out in much the same way whether she was there or not.

The Mandrill’s hate cult has now repackaged itself as terrorist group Black Spectre, although it’s still the same cultists in the uniforms – as far as we can see, they’re still all black women with mandrill patterns tattooed on their faces. That’s not obvious at first, since they wear full body costumes that conceal their gender, let alone their race. But the group is called Black Spectre for a reason. Randomly added to the group as a more colourful henchman is the debuting Silver Samurai, played as a man of honour paying off a debt; despite being well pitched as an opponent for Daredevil and fitting quite well with the iconography of later Daredevil, he doesn’t return, and seems to have been nailed on to the story for no particular reason.

Black Spectre’s big idea is that power lies in symbols. The Mandrill plans to stage a coup in America through a combination of conventional terrorism and situationist pranks. In issues #108-109, Black Spectre steal some printing plates that they can use to print “genuine” American dollars. But we also get a montage of other bizarre schemes. They’ve staged a race riot at the Statue of Liberty. They’ve draped Independence Hall in black to signify mourning. They’ve mounted a swastika on the Washington Monument. They’ve used “some sort of laser device” to add the face of Adolf Hitler to Mount Rushmore. And they hurl their “genuine money” to the public from the rooftops of Wall Street.

At this point the story crosses over into Marvel Two-in-One #3, also written by Gerber. This issue mostly involves Daredevil and the Thing boarding Black Spectre’s airship, and might be seen as a bit of an advert for Daredevil. But it also includes a scene in which Foggy’s younger sister Candace – a would-be radical journalist – drags Matt to an “avant garde pro-patriotism play”. The cast have been hypnotised by Black Spectre. A black man comes on dressed as a slave and berates white people. Another actor dressed as Captain America beats him up, while yelling that America is all aobut treating minorities with respect. “Captain America” is then shot dead by “Adolf Hitler”, who declares “Und now der show is over! America must die!” before committing suicide on stage by shooting himself in the head. This is not the sort of thing we’ve been getting in Gerber’s Daredevil up to this point.

In issue #111, Daredevil finally meets the Mandrill, and this is where things get more problematic. First, the Mandrill explains that the Black Widow has switched sides to join him, thanks to his incredible power over women. “She loves me,” he explains. “All women love me. I am their master.”

This alone puts the Mandrill into very dodgy territory. His power isn’t mind control as such, but women are supposedly unable to resist him – though despite his claims, they generally seem more zombified than smitten. Certainly the Black Widow spends several issues loyally obeying him, with no subterfuge involved. She even tells the Mandrill about Daredevil’s secret identity, a plot thread that seems to have been politely forgotten about by everyone since. Now, in fairness, the Mandrill isn’t shown using his cultists as anything other than cannon fodder – in contrast to the Purple Man, say, who did have a mind-controlled girlfriend when we last saw him. But the Mandrill’s gender-specific powers have nasty overtones nonetheless. As for Shanna, she’s just immune, for reasons that are never explained.

Then we get to the Mandrill’s origin story – and since we’re expressly reminded that Daredevil can tell whether the villain is lying, we’re apparently meant to take it at face value. According to the Mandrill, he and Nekra are the chidlren of a white scientist and a black cleaning lady who were working at an atomic research facility in New Mexico. Both were exposed to radiation in the same incident. The white man’s son is the Mandrill, who was born with black skin and who became more mandrill-like over time. The black woman’s daughter is Nekra, a vampiric albino. Each was rejected by their respective communities. Mandrill was dumped in the desert by his parents, where he stumbled upon Nekra, who had run away from home; presumably we’re meant to take it that they’re somehow drawn together, since otherwise it’s a staggering coincidence. The two bonded, and grew up together as homeless children. They discovered Nekra’s powers after being attacked by a lynch mob. Nekra herself is under the Mandrills’ influence, by the way, which has made it a little easier for later writers to rehab her.

The Mandrill claims that his intention is to “create a near utopia – an alternative to the perverted value system of America”. He never really explains what this will involve, beyond the bare fact that it’ll be some sort of hate-based system. But hold on. Let’s take a step back.

Obviously, the high concept of this origin story is a race swap. The black kid is a monstrous version of whiteness, the white kid is a monstrous version of blackness. Except the story’s version of monstrous whiteness is a hot goth chick. And it’s version of monstrous blackness is, literally and explicitly, a sexually magnetic monkey. Even in 1974, this seemed like a good idea? Really?

Gerber’s idea seems to be that Mandrill and Nekra are both projections of American racial hatred and division, and that they represent a vicious cycle. The white and black communities each have their own prejudices reflected back at them, and they respond by doubling down. That causes Mandrill and Nekra to become even more radicalised, and to become convinced that hate is where all true power ultimately lies in America. Certainly, the moral that Daredevil ultimately draws from the whole thing is the need to break out of that cycle – he regards Mandrill’s origin story as sympathetic, but draws the line at the point where they start killing people. Evidently that’s the message that Gerber thought he was sending with these characters.

But the story is, at the very least, invoking an extremely racist trope, and there’s no real parity between “sex ape” and “vampire chick”. You could argue that this is deliberate, and that Gerber is implying that the racism of black people is less grotesque than the racism of white people, but that feels like a stretch. And the decision to make them radiation-fuelled mutants is odd, since it obscures the fact that they’re apparently meant to be projections of American culture. This story is about symbols, not scientific hubris; surely their origin ought to lie in magic, not pseudo-science.

The story builds to Black Spectre claiming to have a nuke (they’re bluffing) and seizing the White House. The narrator stresses that the White House is just a building, but explains that it’s the climax of a series of attacks on American national symbols which will let the Mandrill subvert the narrative of American national identity. Black Spectre then lower a giant Mandrill statute onto the White House lawn. It doesn’t have a payload. It doesn’t do anything. It’s just a big statue. “He knows the US army could easily overcome Black Spectre by sheer numbers,” says the narrator, “but that does not matter. For war today is fought on the battleground of public relations.”

The plot depends on everyone but Daredevil and his allies caving to the nuclear bluff. That’s also a problem, because if that works, it kind of breaks the genre. And even on the story’s own terms, seizing the White House doesn’t seem to achieve anything. Instead, Daredevil frees the Widow; she gets her revenge by blowing up the Black Spectre airship; and Mandrill escapes while all of his followers are rounded up by the authorities. Perhaps you could make a case that Daredevil gets him out before the damage is done, but it feels awkward. The idea of defeating America by subverting its symbols is interesting, but Gerber never quite works out how to translate that into the climax of a superhero plot, and settles for just blowing everything up.

The Mandrill’s race-swap origin story and gender-specific mind control make him a strong contender for the most disturbing character in the Marvel Universe, and this arc is so strange that you’d have thought it would be a curio. But Mandrill, Nekra and Silver Samurai all had far more staying power than the typical Daredevil villain of this period – albeit not in this book. The Samurai slotted neatly into Wolverine stories. The Mandrill has been relegated to the role of a comedy villain that female heroes get to beat up, which is probably the only way you can use him now. Nekra, who has the excuse of being under Mandrill’s control in this arc, is much more viable on her own and found a new lease of life in the Krakoan-era Exiles team.

It’s a train wreck, to be honest. But it’s hard to look away from.

The idea seems to be that Nekra is fueled by hate, which represents whiteness. But still…

The Mandrill’s later appearances in Defenders make it clear he does use the women under his control as sex-slaves.

This is one of those stories by a white writer that’s trying to be anti-racist but actually winds up being racist. See also,. Englehart’s origin of the Falcon in 1975.

Weirdly. the Mandrill takes control of the Thing at one point despite Ben being male- it’s obvious that Gerber had no idea where he was going with the Mandrill originally and was making things up from issue to issue.

The Mandrill’s later arc in Defenders ends with his mother shooting him and suggesting that she might have been right to leave him for dead. Which is disturbing if you read the Mandrill is a stand-in for black kids with behavioral problems.

The Mandrill later meets Emma Frost, who claims that his problem is that the media tells men like him they can have any beautiful woman they want. The problem with that argument is that the Mandrill’s presented as a victim of child abuse by a parent who got away with it. And Emma has been both the Mandrill and his mother. Emma’s own father abused her and had her and/or her brother institutionalized depending on the writer. That’s usually written as the reason why she became a villain. And Emma abused Angelica Jones and never had to pay for it. (Of course, maternal child abuse doesn’t excuse sexual assault but saying that it’s all the fault of the media when abused children victimize innocent third parties oversimplifies the problem. And Emma is literally the last person who should talk about this issue.)

Nekra is portrayed more sympathetically these days. Although it’s suggested that her anger and revolutionary tendencies when she was with the Mandrill were her own feelings, not a result of the Mandrill’s powers. The problem is she engaged in human sacrifices when she ran a cult of Kali back in Spider-Woman and that’s difficult to justify.

The reason Moondragon left so abruptly is that she was appearing in the Thanos storyline in Captain Marvel.

Re: Mandrill knowing Matt’s identity- it hasn’t so much as been forgotten about as ignored because so many villains found out Matt’s identity. Machinesmith, Purple Man, Kingpin. Typhoid Mary- all of them learned Matt’s identity.It seems like everyone except Bullseye and Owl knew before the period when it became public knowledge- and even Bullseye found out temporarily. In fact, Matt is really bad with keeping his secret in general. I remember as early as the 90s people were making posts about Matt’s “secret” identity.

This can’t be the sort of thing Matt was expecting when he decided to become a superhero.

Silver Samurai’s appearance in this story is odd compared to his later appearances. He’s just a dude with a sword- there’s no suggestion he’s a mutant who can surround it with energy.

There is a mention of a debt his father owes the Mandrill but that’s no explanation of who his father is. We don’t find out it’s Mariko’s father until New Mutants 6.

Oddly. Samurai disappears from the story after Daredevil 111 without any mention.

The one good aspect of the Mandrill’s origin- he’s evil because his mom left him for dead- is now part of Grayson Creed’s origin. Since there’s no problematic racial aspects with Creed, Creed can be used if the writers want a villain like that.

I am quite fond of this storyline, racist elements notwithstanding. I think of it as an early example of themes that will define the Nocenti run later on.

It’s also yet another story in which someone finds out DD’s secret identity and then immediately falls off a roof. But for the first time, it is very clear that the fall didn’t kill the guy, setting up the threat of him returning and using that knowledge.

Beetle is pretty much treated as a long-time DD foe here, if I recall right. He and Silver Samurai could both have been solid recurring additions to DD’s rogues gallery, in another life. It’s not like anyone else was using the Beetle in the ’70s.

Black Spectre as an organisation, on the other hand, don’t really have anywhere to go from here. When the name has been resurrected in later years by e.g. Waid, it’s always been as a generic criminal syndicate, without any suggestion of a political agenda.

Mandrill could easily have become the character Purple Man ended up becoming. Alternatively, it might have made sense to use him as more of an X-men character. The X-Men generally oppose the forcible removal of mutant powers even from villains; Mandrill represents a challenge to that principle.

Regarding Beetle. he pretty much bounced from one title to another for years after he was introduced- he was introduced in Strange Tales 123, appeared next in Amazing Spider-Man 21. then appeared in Fantastic Four Annual 3, then appeared in Avengers 26-28, then Daredevil 33-34. then Amazing Spider-Man 94, then this story. then Daredevil 140, then Spectacular SpIder-Man 16, then Defenders 63-64 ,then Iron Man 126-127 where his armor was wrecked. He got new armor in Spectacular Spider-Man 58-60, then had a cameo in Marvel Two-In-One 96, then joined the Masters of Evil in Avengers 228-230. He next appeared in Amazing Spider-Man 280-281, as the leader of the Sinister Syndicate. You’d think that he’d stay a Spider-Man villain from this point but instead he showed up in Iron Man 223-224 and 227, where his armor got wrecked again. Unfortunately, when he showed up in Fantastic Four 334, he was treated as a joke villain. And when he showed up in Spectacular Spider-Man 164, he was treated as a loser villain. He was mainly a Spider-Man villain from that point forward until he joined the Thunderbolts.

So Beetle’s problem wasn’t that no one was using him. It was the opposite- writers kept using him in different titles and by the time he became a consistent member of Spider-Man’s rogues gallery, he was considered a joke.

As for Silver Samuarai, the problem was that no Daredevil writer used him for three years after this story. so Claremont decided to use him as the Viper’s Dragon in Marvel Team-Up. And he stayed the Viper’s Dragon until 1988, and no one wanted to use the Viper as a DD foe.

Here’s my take: Mandrill is a satire of white racism against Black people.

What does the name Black SPECTRE bring to mind? I think of the Communist Manifesto, “A spectre is haunting Europe”, except instead of Communism haunting Europe, it is the idea of Black Power which was most haunting to white America.

It should be remembered that Mandrill is actually a white guy, regardless of his skin colour (and we’ll ignore the monkey aspect). One of the most pernicious racist stereotypes of Black men was that they are sexually irresistible to white women, but until the Black Widow, all of the Mandrill’s female followers were Black females. Gerber seems to have wrote it as an inverse of how white racism sees the threat of the Black man.

Also, Mandrill’s goal is to take over the American government, which is the gravest fear of white racists in America, that Black people want to take over “their country”.

I agree that Nekra gets short shrift due to Gerber’s satire being mainly aimed at white racists; Mandrill, who is a white man, takes on the dominant destructive stereotypes that racist white people believe of Black people. Nekra, on the other hand, is a Black woman and in Gerber’s mind, he sees a Black person’s racist idea against white folk to be that white people are driven by hatred.

It is a major flaw in the storytelling that Mandrill and Nekra were explained as mutants, as it doesn’t fit with the satire Gerber is trying to tell.

This is another example of a large problem with Gerber’s DD run. He created characters who should never have been brought back afterward, as they were created to represent the point Gerber wanted to make, not as recurring shared universe characters.

I wonder if Gerber oddly stuck Silver Samurai into this arc to appease those who would want to use a character he created in other straight-forward Marvel Universe comics.

I liked Negra when she was Grim Reaper’s co-hort/GF in that Vision/Wanda era of stuff in the 80s.

@Chris V- Spectre was the name of the Evil Organization that James Bond opposed. I think that’s what Gerber was thinking of.

I think the problem with the Mandrill’s power is that it’s basically super-rape and one racist stereotype of black men is that they’re all rapists.

One other weird thing about this story- Foggy concludes that it was Silver Samurai who murdered Shanna’s father but this is later forgotten about. There’s been multiple stories where Wolverine lets Silver Samurai go free and Shanna’s father is never mentioned.

My understanding is that the Silver Samurai vanishes from the story because Gene Colan, who was pulled in to draw #112, either didn’t have access to #111 or didn’t look it over before pencilling his issue. (These were still the days of “Marvel Style” scripting, that is, retroscripting after the artist develops the story from a short plot summary.)

Even in terms of the plot, he’s a pretty incidental character, more an especially threatening henchman than anything else. Pretty much everything about he character comes from Claremont’s revival of him in Marvel Team-Up v.1, which established his powers and partnered him with the Viper.

I suppose that Gerber didn’t have this story planned when he established Nekra and Mandrill as mutants in Shanna the She-Devil v.1. I think Michael is right when he says that a lot of this is just being made up month-to-month. Or, perhaps, Gerber was tapping in to the idea of mutants as a distinctly Marvel Universe sort of marginalized group. So there’s a general theme in place, but the plot mechanics are pretty inconsistent throughout.

As to the trainwreck elements of the story, as Paul so aptly puts it….yes, as Paul explains, the idea does seem to be that “that Mandrill and Nekra are both projections of American racial hatred and division, and that they represent a vicious cycle. The white and black communities each have their own prejudices reflected back at them, and they respond by doubling down.” This not only fits the general presentation of their origin, but also the villains’ emphasis on big, symbolic gestures as a method of revolution.

But the problem is not only that the Mandrill plays into a much more established, much more destructive stereotype, but also that Black Spectre ends up creating an army of essentially voiceless, will-less, and horribly dehumanized Black women.

But then the story simply has no interest in them, not even touching on what would surely be the horrible trauma of being mind-controlled into terrorism and then permanently facially marked with tattoos that make them look like apes. Like, what happens to them after the Mandrill is defeated and runs off?

Instead, the focus is on how Shanna and the Black Widow react to the Mandrill…the two white women in the story. It’s a serious, troubling problem with the story that simply goes unremarked and unacknowledged.

In any case, it does seem like Nekra’s look helped her a lot. She turns up in Spider-Woman next, where Mark Gruenwald uses her to tie in the Cult of Kali from some of the earliest Iron Fist stories in Marvel Premiere v.1, and then she’s next used by Gerber’s old buddy Steve Engelhart in West Coasy Avengers v.1.

Engelhart actually does play with the racial themes a bit: This is the story that plays off of the reveal of the Grim reaper’s racism, with him taking Nekra as a lover and explicitly denying her Black heritage, while also disparaging his allies the Black Talon adn the Man-Ape.

Of course, his henchman being a pair of characters with their own stereotypical archetypes doesn’t help much, even when the Reaper loses partly because they walk away from him in disgust. And then the follow-up, with Nekra becoming a voodoo priestess who raises zombies, arguably hits similar problems. But that kept her around as a villain; the vampiric look and the codename fit well with raising the dead.

Mandrill, on the other hand, bounces through a couple of linked storylines in Ed Hannigan’s run scripting Defenders, a run that wasn’t popular at the time and is mostly forgotten today. And those stories seem to be about doubling down on how loathsome he is, as Michael notes above.

Roy Thomas tried to write both Nekra and the Mandrill out in the 1990s, having his vampiric version of the Grim Reaper kill them both in his own West Coast Avengers run. But Nekra was back just a few years later, now played wholly as a supernatural character. And, significantly, no one pairs her with the Mandrill any more, so she’s gotten some distance from the origin Gerber wrote. At most, you’ll read some dialogue or captions establishing that she’s a mutant.

The Mandrill took a lot longer to come back after he died. I think it may have been Bendis who used him next as something beyond a silent face in a crowd, and that’s where he started being played as something between a joke and a character whose creepier aspects were played up. But he’s just never been as prominent as Nekra, likely because his power is so gross and because the visual is both problematic and ridiculous in multiple ways.

@Omar- Mandrill reappeared in Alpha Flight 121, by Simon Forman and E. Craig Brasfield, which was one of those issues that featured a lot of villains that were thrown in without regard for continuity. Black Tom Cassidy was supposed to appear but the X-books complained because he was going to appear in a Deadpool limited series, which should have come as no surprise to the creators since his last appearance involved a wounded Black Tom being handed over by Deadpool to a mysterious employer. So he got replaced by a cut-and-paste of Caliber.

Similarly, Harry Osborn as the Green Goblin was supposed to appear but he was being killed off in Spectacular Spider-Man at the time, so he had to be removed.

Ghost Rider’s Blackout appeared in the issue even though he was temporarily dead and in the process of being revived by Lilith.

This is a problem that crops up in popular culture when attempting to lampoon racist/stereotypical ideas about white folk versus Black people. The racist assumptions about white people are mostly inoffensive. All white people are a bunch of hate-filled racists is the most negative idea by biased African-Americans about white Americans.

Otherwise, we see stereotypes such as white people are stuffy intellectuals, they can’t dance, and they can’t play sports. So hurtful. These stereotypes about white people seem to be more about feeding back into pervasive ideas about Black people more than a direct attack on white culture or “whiteness”. Intellectuals cannot be Black people? Are Black people always “cool” and good at sports? Certainly not.

Just musing on how odd the idea of finishing a cancelled book’s in another title is. A book is cancelled because people don’t want to read it. Why take its failed content and shoehorn it into another, still-viable book? Only in comics…

@Joe S. Walker- often, because writers want to finish the stories they started.

@Joe S. Walker: This was a really big thing at Marvel and DC in the 1970s and 1980s, when cancellations were sometimes rather abrupt.

So, for example, Gerber’s cancelled Omega the Unknown was wrapped up unsatisfactorily by another writer in some stray issues of Defenders, the cancelled Secret Society of Super-Villains finally got theirs in a three-parter in Justice League of America, and a few loose ends from the Invaders series were tied off in the Roger Stern/John Byrne run on Captain America.

Steve Engelhart, Roy Thomas, and Jim Starlin were especially willing to use their newest book to finish plotlines from books they’d left, or which had been cancelled out from under them.

So various cliffhangers and plot setups from the truncated Beast serial from Amazing Adventures were wrapped up in various issues of Incredible Hulk, Captain America, and Avengers, since those were the books Engelhart was working on after his Beast run was cut short.

More famously, Starlin wrapped up his Thanos saga from Warlock series in a crossover from an Avengers Annual into a Marvel Two-In-One Annual.

This is one fo the few times I remember Gerber explicitly finishing a truncated storyline from a book he’d written in the book he was now writing. But that’s generally because Gerber uusally finished his plotlines up, often in deliberately absurd, anticlimactic ways.

Michael’s probably right the writers want to finish a story they’ve started, but I wonder if it isn’t also because it’s one less issue (or however many issues they can string it out over) they have to come up with a plot for the new book they’re writing.

In this case, I assume Gerber knew what he wanted to do with this idea, so it was just a matter of fitting it (however awkwardly) into Daredevil.

Also, this is silly, but when I saw Black Spectre, my first thought was, “Moon Knight swiped one of Daredevil’s castoffs for his own rogue’s gallery?” Wrong Black Spectre, though. (Kind of thought one of them would spell it differently, at least.)

When I started collecting Fantastic Four, there was an enormous storyline that seemed to come out of nowhere full of characters and situations I didn’t know at all. I read it all just the same, and only later found out that it was the wrap-up of Marv Wolfman’s Nova series that he had dragged into his FF.

@Karl_H- the Nova characters appearing in the Fantastic Four doesn’t count. This website explains what happened:

http://www.kleefeldoncomics.com/2012/06/old-wolfmanwein-interview.html

There was a crossover planned between Nova and the Fantastic Four and then Nova got cancelled at the last minute. So all the Nova plots had to be moved into the Fantastic Four.

These things sometimes happened in the late ’70s. Another hilarious example- it was decided Ms. Marvel would join the Avengers to boost her sales but by the time she officially joined, her series was cancelled.

It’s odd that the Beetle is involved (even is it is to the side of the main story) in an arc that involves a race swap story line considering his future in the Thunderbolts.

@Michael: Marvel was kind of a mess behind the scenes for a lot of the 1970s, from what I’ve read. They couldn’t keep anyone in the EiC position for long, a lot of writers were either formally or de facto editing their own work, and inflationary pressures kept forcing cancellations and format or price changes.

I think there’s even an issue of Fantastic Four set at the Marvel offices that shows a bunch of names crossed out on the editor-in-chief’s door.

It took a few years of Jim Shooter as Editor-in-Chief to stabilize scheduling, editorial processes, and editorial personnel.

And, of course, Shooter alienated and a lot of people with his heavy-handed management style and his corporate mentality, including his increasing interventions into creative decisions, and eventually ended up pushed out of Marvel entirely.

@Omar Karindu, @Joe S. Walker: Even more brazenly, there was the time Steve Skeates started a story in Aquaman #56, which turned out to be the last issue of the series. He picked up the story two years later in Sub-Mariner #72.

@Omar Karindu: Shooter may have been heavy-handed, but that might have been exactly what Marvel needed. My sense is that he brought a sense of professionalism to Marvel’s offices for the first time, managed to increase sales, and instituted a decent royalty scheme for creators.

@Taibak: I think Shooter was exactly what Marvel needed coming out of the 1970s. Some of the people who disliked him — Roy Thomas, Marv Wolfman, and Len Wein — were in no small part upset that he eliminated the practice of the writer-editor, the writer getting to edit their own work.

But I think Shooter, at a certain point, got too full of himself and too invested in chain-of-command. By all accounts, he started micromanaging storytelling decisions more and more frequently.

He also looks bad, in retrospect, when compared to Paul Levitz at DC Comics. Shooter did help develop Marvel’s royalties program, but that program was much less generous than DC’s from the same era. Even today, writers state that they make much more from royalties from media adaptations of their DC creations than from Marvel movies, which apparently pay nothing but a token fee, and that is done voluntarily rather than by contract.

Shootter was also entangled witht he conroversy over Marvel refusing to return original artwork to creators, including Jack Kirby. By contrast, Levitz went out of his way to ensure that Kirby was given the opportunity to redesign some of his Fourth World characters for a comic, allowing Kirby to receive money from upcoming toy and animation licensing of those characters. This helped Kirby avoid being left out of some of the royalties because he’d created his characters before that policy was brought in.

Now, I don’t now how much of this is Shooter, and how much was Marvel’s crappy corporate management under Cadence and later CarolCo. And where DC’s publisher was the experienced magazine manager Jeanette Kahn, who brought in or approved policies that benefitted creators, Marvel’s publisher during Shooter’s tenure and beyond was rarely of the same background or mindset.

And, of course, Shooter’s own creative instincts seem to have gone wrong during the later parts of his time as Marvel’s EiC. He went from being the guy who righted the ship, put Frank Miller on Daredevil, and approved putting Walt Simonson on Thor to the guy who made everyone cross over with Secret Wars II and launched the failed New Universe line. This didn’t help when he continued micromanaging writing decisions on various titles.

So the net effect is that Shooter not only got into a lot of feuds with specific, big-name creators, but also ended up being the face of Marvel’s nasty corporate side. None of that has helped his reputation, in retrospect.

Some of my references to Paul Levotz should either include or be replaced with references to Jenette Kahn.

Yes, but it’s weird how some editors avoid being judged harshly like Shooter was.Take Mark Gruenwald. He does deserve considerable blame for the Avenngers’ decline in the late 80s and early-to-mid 90s. He fired Roger Stern off the Avengers so that Captain America could be installed as the Avengers’ leader and replace Monica Rambeau, who was the Avengers’ leader at the time. Gruenwald did this to boost sales in Cap’s book, which was written by… Mark Gruenwald. This would have never happened if Gruenwald wasn’t the editor- firing a popular writer off a high-selling book to help a low-selling book was unheard of. But Gruenwald was blind to the conflict of interest between his role as writer of Captain America and editor of the Avengers. That was the start of the Avengers’ decline in both sales and quality. Later on, in 1995, he was the editor in charge of the Crossing, which is often considered the worst Avengers story ever. But Gruenwald is often remembered as the editor in charge of the Avengers’ glory days in the ’80s, which he DOES deserve a lot of credit for, and not for his mistakes. In Gruenwald’s case. it’s largely because he died young.

There’s also Tom DeFalco. He was Marvel’s Editor-in-Chief from 1987 to 1994 and he was largely responsible for the mess that Marvel turned into during the early 1990s. Sales completely collapsed by the end of his tenure- classic Marvel titles like Captain America, Thor, Fantastic Four, Iron Man and Avengers were selling at historic lows at the end of his term. In its first 40 years, the Fantastic Four was always one of Marvel’s top 10 sellers, except for two periods- when DeFalco was writing and when Englehart was writing (most of which was under DeFalco’s stint as Editor-In-Chief). In addition to writing Fantastic Four during this period, he also wrote Thor up to 1992, and helped contribute to its decline. (Although after he left, Ron Marz took over and wrote an insane Thor trying to destroy the universe, so DeFalco’s wiriting doesn’t deserve all the blame. This was one case where Ron Marz having a beloved Silver Age hero go insane actually drove away readers.) In fact, that was one of the flaws of DeFalco’s tenure- editors were allowed to stay on once-popular titles long after sales had collapsed- DeFalco on Thor and Fantastic Four, Gruenwald on Captain America and Harras on Avengers. In fact, one of the positive features of Harras’s stint as Editor-in-Chief is that he revived sales on Marvel’s classic titles- Avengers, Fantastic Four, Iron Man, Thor, Captain America and Daredevil. DeFalco also approved the Clone Saga and was one of the writers. He was the only Editor-In-Chief whose tenure can objectively be called a failure. Yet Defalco is often judged less harshly than Shooter. Like Shooter with Hank and Jan, DeFalco had Peter hit MJ (a few months after he had been fired as Editor-in-Chief) and both DeFalco and Shooter blamed the artists but amazingly, DeFalco having Peter hit MJ is treated with more grace than Shooter having Hank hit Jan.

The X-Men revival was already in the works when this story was published, which is why there’s a spate of new mutant characters appearing around this time, as well as the X-Men and other established mutants popping up in odd places. There may have been editorial encouragement to create more mutants, so writers gave their characters mutant backgrounds.

I strongly suspect Silver Samurai was actually a Claremont creation, which is why he’s mostly superfluous to this story and is never used by Gerber or any DD writer again. In addition to the fill-in issue Claremont wrote, I got the impression he may have had other input in Gerber’s run: maybe he was in effect the assistant editor on the series. Angar, of course, next shows up in a Claremont story. I’m sure Gerber created the LSD hippie villain, but Claremont seems to have felt like he had a connection to Angar, too. (And now that I think of it, when Claremont introduces Siryn, her powers are different from her father’s in that she has something like this hallucinogenic effect. Hmm…)

Anyway, my money’s on the Samurai being a Claremont creation, even if Gerber first wrote him.

I just realised the Daredevil comic has one of my favourite comic things; fake-profound quotes. “Murder! Cries the Mandrill!” What the hell does that even mean? I haven’t read the comic, maybe Mandrill does indeed yell “Murder!” But either way, I really do like it.

@Michael The effects of DeFalco’s role as EiC are maybe harder to separate from or overshadowed by the boom and bust taking place in the comics market at the time.

Also Shooter seems to have been more personally abrasive to a lot of writers (i.e. people who have experience in providing personal characterisations).

@Michael: I think Shooter’s problem was that he managed to tick off high-profile creators who then openly spoke out against him, and that he ended up (at least appearing to be) on the wrong end of the creators’ rights controversy, with no less than Jack Kirby himself on the other side, and vocally so.

In contrast, Gruenwald may have blown it badly by firing Roger Stern, but he was relatively transparent at the time about why. He couched it as Stern not wanting to shift the Avengers title, and especially Monica Rambeau, in a direction that had been agreed on by not only Gruenwald but also writers of other titles.

And while the quality of the Avengers books certainly declined in the aftermath, at the time the net effect was to get Walt Simonson in as a replacement on the main Avengers title and to bring back John Byrne shortly thereafter. So to fans at the time, it was big-name creators coming back. And Byrne was not only one of them, but had spent years making sure everyone knew that he’d been driven away from Marvel by Shooter.

But most of all, Gruenwald was, I think, widely beloved by fans as the Last Marvelite in the later 1990s, a guy whose writing was past its prime, but who cared about continuity and classic storytelling and so forth. His early death did cement that as part of his legacy, but he also seems to have generally gotten along with most people in a way Shooter didn’t.

His firing of Roger Stern and his insistence on staying on Captain America too long are the big criticism of him that have stuck. But no one sees him as a petty tyrant the way may creators very publicly seem to have described Jim Shooter.

DeFalco, I think, gets a but of a pass because most fans don’t see him as being in full control. The Clone Saga was at least partly extended by marketing demands, for example, and a lot more of the blame for problems in DeFalco’s era seem to be blamed on Ron Perelman and the ToyBiz execs.

I think DeFalco also gets less personalized heat from fans because the time period when he was EiC is retrospectively seen as a creative nadir for superhero comics at both companies. DeFalco’s successor, Bob Harras also isn’t seen as an especially successful or beloved EiC, for instance, and many of DC’s books of the same eras — pretty much everything in the post-Giffen/DeMatteis, Pre-Morrison Justice League titles, for instance; and the late-period Wolfman work on the Titans franchise — are not fondly remembered, either.

DeFalco did manage to seriously anger Steve Engelhart with his refusal to allow the Mantis character back in print, but few fans would forcefully defend Engelhart’s insistence on using the character. To the extent that Engelhart damaged FF sales, DeFalco was no small part of Engelhart bailing on that book. And, again, Simonson and Byrne came in after Engelhart, as did Jim Starlin, which helped fan perception quite a bit (even if there’s a lot of distaste for some of Byrne’s West Coast Avengers story decisions in some quarters, including mine).

I would say that DeFalco is not seen as a great writer. His early 1990s Thor and Thunderstrike runs have some fans, but for the most part his post-1980s work is not well-loved. Spider-Girl benefitted greatly from being an alternative to the Mackie/Byrne attempt at writing out Spider-Man’s marriage and Byrne’s implementation of various unpopular retcons. But DeFalco isn’t generally regarded as much beyond a sometimes fun, often hokey, and sometimes crummy writer.

And I’d say that both Gruenwald and DeFalco benefit from not being the ones blamed for the decline and fall of the X-books, which were then Marvels’ most popular titles by far. That seems to have fallen more squarely on Bob Harras in fan estimation, fairly or not.

Overall, I think Jim Shooter suffers for being an Editor-in-Chief who really was seen as “in charge,” for making some questionable linewide decisions rather than decisions that were just bad for specific books, and because he seems to have inspired especially vocal and public anger on the part of superstar creators, often at the heights of their popularity, in ways others did not.

@Wakter Lawson: I think Claremont was unoffically tasked as Gerber’s assistant for a while back when the former was trying to break in at Marvel as a writer. Clarmeont also revived and fleshed out Radion, a Gerber co-creation from Marvel Two-in-One, in his Iron Fist stories.

That said, in the 1970s and early 1980s, Claremont sometimes just picked up characters he liked and ran with them. For example, after he and John Bryne revived Boomerang in Iron Fist, Claremont brought the assassin over into a multi-parter in Marvel Team-Up. These two are interesting because Claremont then pretty well dropped them both.

Around the same time, Claremont wholly adopted the Viper, who’d started as Jim Steranko’s late 1960s creation Madame Hydra and then gotten a revamp in Steve Engelhart’s Captain America. Claremont started using the Viper in Marvel Team-Up, pairing her with the Silver Samurai, and then kept bringing her into his other books. This is how the Viper has ended up halfway in the X-books and how she was tied to Jessica Drew.

Claremont also picked up characters like Garokk the Petrified Man and Zaladane from the early 1970s Ka-Zar series in Astonishing Tales, making them his own, though there’s an argument that their ties to the Savage Land indirectly connected them to the X-Men books.

There are also more minor examples, like the way henry Peter Gyrich was halfway drafted into the X-books after being introduced as a thorn in the Avengers’ collective side.

I do think that by the mid-to-late 1980s, Claremont had woven a pretty self-contained mythos out of the X-titles, so this kind of adoption of preexisting characters or other folks’ creations slowed way down. After that, he only retained an interest in characters he’d already “adopted” or whom he’d previously written for in their own titles.

Well, which creators, in particular, have criticized Shooter? I know John Byrne isn’t a fan of his, but Byrne seems to have issues with a lot of people in the industry. Put another way, how much of the criticism is coming from people like, say, Marv Wolfman who were angry that Shooter wouldn’t let them edit their own books?

And if Harris and DeFalco come across better, how much of that is because they came after Shooter and weren’t the ones having to impose some professional standards on the company?

I think the fact that creators working in the era loathed Shooter definitely does have a big effect. But managing those personalities was a lot of the job that Shooter was being paid to do. With Shooter, there seems to have been an element of being really good at some aspects of being in charge, but very bad at others.

To pick an admittedly egregious example, the decision to write Secret Wars himself was inevitably going to make people angry after he’d forbidden the practice to other people. The reason that he gives could certainly be genuine, but it’s not a good enough reason to justify the decision. It’s a basic thing about leadership that everyone gets that you might be able to persuade people that the situation needs an iron hand to make the trains run on time, but not if you’re going to give yourself a first-class ticket – you have to obey the rules that you lay down for others.

Taibak: for details on this, including people speaking on the record, Sean Howe’s Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, is pretty good, I think.

On one level, shooter’s most successful writing was prob on the Legion, so he knew how to write a series with dozens of characters in it.

But, the boss choosing to write a sure to be mega series is bad optics.

If I recall correctly Marvel royalties and film residuals are worse than Levitiz’s because Marvel’s stuff was codified to be a certain way and Levitiz was deliberately more generous on a case-by-case business and was empowered to be so. Levitiz had no obligation to be so but felt it was right; apparently the residuals dropped off when he retired/died.

I’m going by memory here.

@Mark Coale: I think Shooter’s writing on his first run of Avengers is highly regarded as well, as is some of his work in setting up the parameters of the Valiant universe.

@Walter Lawson: After I posted, I also remembered that Moses Magnum was another minor 70s character that Claremont picked up and made his own, bringing back the Gerry Conway/Ross Andru co-creation in, of all things, the only Power Man Annual Marvel ever published, where he used machines to set up earthquakes as was surreptitiously opposed by the “Council of the Chosen” that later became the Hellfire Club. And, of course, Magnum turns up with his now-signature earthquake powers — he was using an earthquake machine in the Power Man story — in the Claremont/Byrne Uncanny X-Men, where Magnum is the plot device used to remove Banshee’s powers.

Claremont also picked up Magnum’s evil arms dealing firm, the Deterrence Research Corporation, from the Conway-Andru Spider-Man story, creating a new president for them — Ivor Carlson — and having them recruit and reoutfit one-off Hulk villains Hammer and Anvil (introduced in the same issue as, but unrelated to Wolverine’s third published appearance) as their main henchmen. The DRC and Hammer and Anvil bounced through a couple of Claremont’s Marvel Team-Up and Spider-Woman stories.

As with the other 1970s minor-leaguers Claremont borrowed from other writers, Magnum, the DRC, and Hammer and Anvil drop out of Claremont’s stories as his X-universe becomes more self-contained in the 1980s.

Magnum shows up just once more in a Claremont X-title via a Classic X-Men reprint interpolation that retcons his earthquake powers into a gift from Apocalypse. Magnum’s powers had previously been established as the work of “They Who Wield Power” in Roger Sterns’ Incredible Hulk stories a few years prior, well before Apocalypse was even created. (Perhaps this can be resolved if we assume Magnum’s earlier earthquake machine and high-tech battlesuit from Power Man Annual #1 are from “They.”)

There’s also Jim Shooter’s own views on his defunct blog jimshooter.com, and the latest entry on it linked to a third-party defense of him.

I question whether the original Secret Wars was going to be a surefire hit since it was a toy tie-in series. As later crossover/events have had one team clearly in the driver’s seat, I think having someone unrelated to either side writing it, though they’ve went to the well of “hero team A fights hero team B until maybe the last issue where they might team up against the force that was manipulating them all along” far too many times.

Have the Marvel royalty rates been updated since they were established? Per Shooter’s blog, they kicked it at a particular sales level (I don’t think any current series would meet that level, at the time he claimed all or nearly all titles hit that sales level). I think it’s on later EiCs to update those rates.

If I recall, Warhawk was also a Power Man and Iron Fist villain that had that one appearance in Uncanny X-Men #110 (referenced in the Dark Phoenix Saga, but not reprinted in Classic X-Men because I think it was licensed as a reprint?). He was employed by the Hellfire Club, though it may have been called the Council of the Chosen at the time.

On the Council of the Chosen during the time period they were called that (reference in Claremont’s first Sentinel story as being behind Lang), it kind of felt like they were Claremont’s take on a Roxxon/the Corporation villainous organization and then somewhere along the line (maybe at John Byrne’s input) they got changed into the full-fledged supervillain team that we know and love as the Inner Circle of the Hellfire Club. Or am I the only one who interpreted it that way?

@Sam- it was trying into most of the major Marvel books- Spider-Man, Hulk, Fantastic Four, Avengers. X-Men. And it featured a new costume for Spider-Man. It was pretty much guaranteed to be a major seller.

@Sam: Yeah, the Council of the Chosen start out as a shadowy group of conspirators. The Hellfire Club stuff comes in after Byrne is on board, and their chess motif isn’t fully established even in their first appearance. The only reason they have a White and Black Queen is that they’re a cute riff on an episode of the 1960s British spy show The Avengers.

Regarding Warhawk, he was a Claremont co-creation. He not only turned up in that issue of Uncanny X-Men, but was also meant to be the mysterious assassin seen in Black Goliath #2-3, which Claremont wrote. However, Warhawk, like Sabretooth, was taken up by later writers on Power Man and Iron Fist — a book Claremont had helped get started — and had his origin tied to Luke Cage’s.

Last week Tom De Falco spoke about Secret Wars during the Official Marvel Podcast (he was the editor of the series), and he said that at the time they didn’t foresee it being a success, rather the opposite

Ah Warhawk. One of the earlier X-Men comics I read was a local reprint of that issue, with much cheaper printing that made the already poor pallete of the character particularly hideous. And he was being ordered around by a shadowy face that somehow looked just like Warhawk. And so did Colossus, they were all light blue guys so I figured there was some link. But what? I never knew, and later got the memory mixed up with Mr Sinister.

Later it turns out they never revealed who he was working for, except in a footnote in a comic that came out years later. Claremont’s gonna Claremont.

@Si: During the Dark Phoenix Saga, Mastermind does manage to say “Your man Warhawk did his bugging well” to Sebastian Shaw. Of course, it’s in issue #129, so “years later” is right on the money.

One other factor to keep in mind when comparing the different royalty programs: DC is owned by the same conglomerate that owns Warner Bros. and has been since 1969. Marvel never had that kind of financial backstop until 2009, when it was bought by Disney.

Granted, DC was in rough financial shape in the late 70s and early 80s, but I wouldn’t be surprised if DC’s corporate overlords gave it

much more room to be generous with royalties than Marvel’s did.